Youth Civic Empowerment

Youth Civic Engagement & Health

Civic Empowerment is a Path to Healthier Youth

Research on the relationship between civic engagement and health is still nascent but increasingly revealing the connection between the two. Health-focused foundations and institutions across the nation are beginning to invest in civic leadership to improve health outcomes and improve community health overall.[i],[ii],[iii] The field acknowledges that youth are a particularly important population to focus on. They are often left out of decision-making processes and yet represent the future leaders of our communities.

The Problem & Opportunity

San Mateo County has seen concerning data on increasing depression and disconnection in our youth. Disconnected youth who feel like they have little agency are more likely to use alcohol and other drugs, engage in other risky behavior and do poorly in school. To improve health, we need to identify ways for our youth to feel more connected and empowered. Civic empowerment offers one path to healthier youth.

Social connection is vital for healthy people and communities. Research shows that stronger sense of belonging could lead to better health outcomes and communities with higher levels of social cohesion are more likely to identify their needs and find solutions to their problems.[iv],[v]

In contrast, social isolation is bad for health. There are negative physical and mental health outcomes associated with social isolation that individuals across ages may experience, such as a higher risk of depression,[vi] increased use of substances, or even increased risk of premature death.[vii]

People across the nation are experiencing more loneliness and social isolation. Some key national indicators of community and connection, such as voting, volunteerism, and participation in religious, political, or social organizations have all been steadily declining.[viii],[ix],[x]

In California, youth voter turnout (ages between 18 and 24) has been declining until 2016, but even with the increases since then, youth eligible turnout is still low and much lower than the voter turnout of the older population.[xi] Similarly, in San Mateo County, youth vote at much lower rates than the general population. In the 2018 general election, the eligible voter turnout for youth was 33.8% compared to 58.6% for the total population.[xii] This means that two thirds of San Mateo County eligible youth voters are not registered to vote or casting their votes.

Building a strong sense of community, where we build connections and feel like we belong, is an important antidote to the increasing social isolation. If people have a greater sense of belonging, they feel that they can be agents of change for their well-being as well as the well-being of their community. Belonging refers to having access and power to influence the communities we interact with.[xiii]

Engaging in civic activities that aim to promote better quality of life for all communities is one way to improve the sense of belonging and increase collective efficacy. By expanding opportunities for youth to engage in civic activities such as volunteering, voting, particularly among youth, we can enhance their sense of belonging and civic empowerment. They can become ambassadors of the needs and aspirations of their communities. Youth that engage in civic activities early on, are more likely to be civically engaged into adulthood.[xiv]

Civic empowerment is a sense of agency to claim one’s own rights to engage in activities related to their community, school, city or town and influence their environments. Civic empowerment enables youth to inform policies and programs that create the conditions for health. It’s also a necessary component to cultivate a thriving diverse democracy. Youth with higher sense of agency have higher rates of civic participation. 14

Civic empowerment is nurtured through civic activities[xv] such as:

Formal policy or political participation

- Voting

- Participating in institutional and public decision-making bodies

- Working on advocacy and political campaigns

- Contacting elected and appointed officials

Participation in civic and community organizations, clubs, boards, political parties

- Volunteering and group membership

- Engaging in online activism and organizing

- Engaging youth through art and other forms of creative expression to foster healing and hope in civic participation

- Engaging in activism to advance social change

Everyday civic engagement

- Engaging with and organizing community members and neighbors

The Health Connection:

How civic empowerment impacts health?

Youth that are civically empowered show a stronger sense of connection to others,[xvi],[xvii],[xviii] which in turn has positive physical and mental health outcomes.17,[xix],[xx]

“Civic engagement has impacted my health and well-being by a good amount. It kinda forces me to go out and while doing that I interact with other people. We are all focusing on one problem and we can all work together to fix it. It’s helped my mental health by allowing me to know why things are happening and that we can do something to fix it.” -Daisy, 15, Half Moon Bay

What are the health benefits of feeling more connected?

Stronger connection to others is associated to:

- better physical and mental health outcomes

- building resiliency in trauma, which translates to better health outcomes.[xxiv]

Alternatively, youth who feel disconnected from their community experience higher levels of isolation and loneliness, which are detrimental to health because:

- it reduces emotional and socio-cognitive competencies.17

- it is associated with psychological symptoms like depression[xxv] and suicide ideation[xxvi]

- it may increase violent behaviors and use of substances.[xxvii],[xxviii],[xxix]

- it is associated with higher risks of premature death.[xxx]

Local Prognosis:

Why does youth civic empowerment matter in San Mateo County?

Local data on youth well-being indicates concerning trends that may be indicative of increasing loneliness and social isolation of youth.

More San Mateo County youth are experiencing

depression.

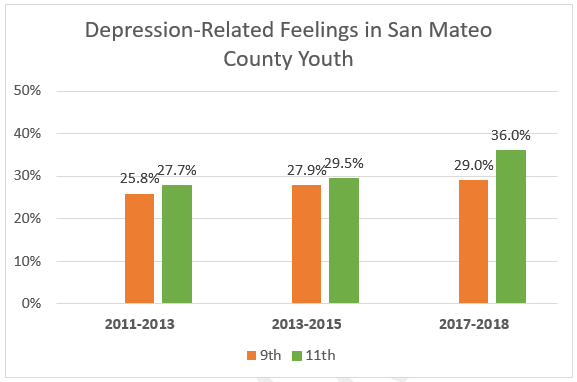

he rate of depression-related feelings is increasing for San

Mateo County youth in grades 9th and 11th.

There is an almost 10% increase for 11th graders since

2011.[xxxi]

Source: California Healthy Kids Survey. Analysis done by

Epidemiology, San Mateo County Health.

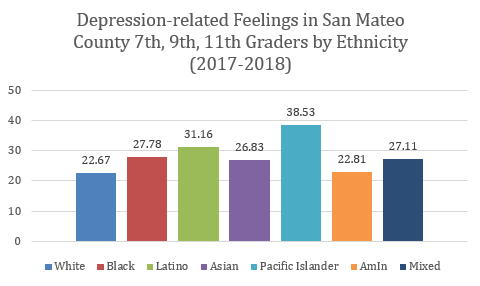

San Mateo County youth of color experience depression at

rates significantly higher than their youth

counterparts.

For example, Pacific Islander youth are 15% more likely to

experience depression than their white classmates.[xxxii]

Source: California Healthy Kids Survey (2017-2018) of 7th, 9th,

and 11th graders. Analysis done by Epidemiology, San Mateo County

Health.

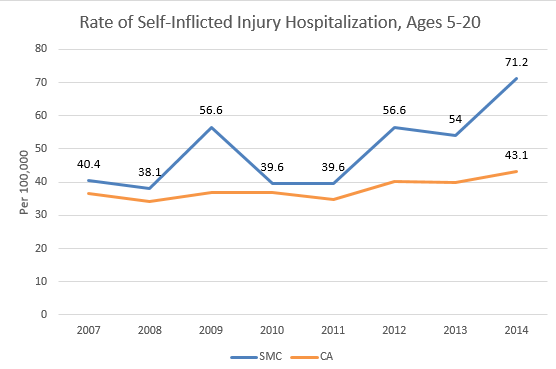

More San Mateo County youth are hospitalized for

self-harm injuries.

The rate of hospitalization for self-inflicted injuries among

youth ages 5 to 20 years old in San Mateo County remains higher

than the rate for California and was nearly 30 percent higher

than the state average in 2014. [xxxiii]

Source: California Department of Public Health, Office

of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Patient

Discharge Data; California Dept. of Finance, Race/Ethnic

Population with Age and Sex Detail, 1990-1999, 2000-2010,

2010-2060; CDC, WISQARS (Apr. 2016)

The Obstacles:

Barriers exist for youth to develop a stronger sense of belonging and civic empowerment.

Youth are having less opportunities to develop their civic knowledge and skills.14

- Education on civics has been declining nationwide.

Youth have limited access to educate themselves about the social, cultural, and political structures and institutions that shape their lives and communities. In addition, information on how to navigate those civic structures are rare and unequally distributed. Youth of color and those who come from low-income communities are at greatest risk of low civic education, which translates in less opportunities to develop and practice communication, analysis, organization, and leadership skills to feel civically empowered.14, [xxxiv]

- Many youth live in places with low opportunities for civic engagement.

A nationwide report indicates that 60% of youth living in rural areas, almost 32% of suburban youth, and 30% of urban youth live in areas with low opportunities for civic engagement or as the report calls these areas “civic deserts”. Civic deserts are places that have little to no investment in civic education and institutions or programs such as arts and culture, or religious or political organizations for youth to engage with.8

- Many youth face barriers to engaging in or with decision-making bodies

According to a local report and our own additional analysis, only 13 out of 21 jurisdictions in San Mateo County have a youth advisory board or council. Few of these councils directly advise policy making bodies but rather they focus on advising local jurisdictions on teen and youth programs and services. 75 out of the 125 commissions examined in the report (60%) hold their meetings during school hours making it very difficult if not impossible for youth to participate. Lastly, commission positions are typically 2-4 years long which may limit participation from young people.[xxxv]

- Public trust in government remains low across generations[xxxvi]

A combination of factors, including, growing distrust in government, is to blame for why so many young eligible voters are not registering to vote or casting their vote. Public trust in government is closely linked to civic engagement, interestingly, in both ways, as a force that could motive or discourage citizens from voting.[xxxvii] Nationwide, youth voter turnout increased significantly since 2014,37 and so did San Mateo County’s youth voter turnout12, despite growing distrust in government. Yet, despite these significant increases, the eligible youth voter turnout for the 2018 general elections was still very low and much lower than the turnout of eligible older voters. National eligible youth voter turnout (ages 18-29) was 28%.[xxxviii] In California, the youth (ages 18-24) eligible voter turnout was 27.5% compared to older adults (ages 65-74) who voted at 68.4%.[xxxix] In San Mateo County, the eligible youth turnout (ages 18-24) was 33.4% compared to eligible older adult voters (ages 65 and above) whose turnout was 72.6%.12 This means that still two thirds of San Mateo County eligible youth voters are not registered to vote or casting their votes.

“Civic engagement had helped me a lot. Sometimes I feel like people don’t take youth’s opinions into account, so it has helped me a lot with getting my voice heard. Another reason that civic engagement has helped us learn how about the behind the scenes of how Half Moon Bay works.” -Socorro, 15, Half Moon Bay

The Prescription:

How do we enhance youth civic empowerment and belonging?

-

Reinvigorate civic education in classrooms in all grades and in all classrooms.

- Incorporate and strengthen civic education into classroom curriculum at all ages.[xl] Research shows that students who receive adequate civic education are more likely to be engaged as active citizens.34

- Develop student projects assignments that relate to civic activities such as attending a city council or school board meeting and volunteering for a cause or campaign.

- Encourage student leadership in the schools and classrooms by developing experiential learning opportunities such as student elections for class mayor or city council.

-

Connect youth to youth development organizations

focused on youth-lead activities.

- Partner with youth development organizations to register youth to vote and support their understanding of why voting matters and how to make sure their voices are counted.

- Encourage community and networks among youth, where they can come together, build upon leadership skills, learn about civic structures, and support collective engagement in civic activities.[xli]

- Develop plans for youth-lead research opportunities where youth collect local information to gain an understanding of the needs and aspirations of their fellow youth. Support their analysis of the research to be shared with community decision-makers.

-

Create meaningful and culturally appropriate

opportunities for youth to become ambassadors of their

communities.

- Support youth to share their ideas, knowledge and experiences by creating youth advisory boards and adding youth voting member seats to existing boards and commissions.35

- Partner youth with adult allies to support their leadership development and build trust, appreciation, creativity and innovation between youth and adults.35,[xlii]

- Develop a process to encourage inclusive representation by collecting and reporting demographic data on boards and commissions.35

-

Meet youth where they are.

- Use online platforms to engage with youth and encourage them to participate in civic engagement activities, ex. Donating, organizing volunteer opportunities, signing petitions, voice political opinion, reading online news sources.[xliii]

- Promote youth-targeted social media and materials to continue to educate youth to participate in civic activities.35

- Making voting registration automatic as soon as a citizen turns 18 and encourage more youth to pre-register online to vote before turning 18.

- Nurture civic empowerment in the school environment by supporting schools to focus on civic activities and build connections among all youth.

Conclusion:

As more youth are struggling with feelings of depression, it is important that we are intentional in developing opportunities for youth. Cultivating civic empowerment is important for everyone but especially for youth as they struggle through a sensitive developmental stage to shape their own identity and sense of belonging.

Expanding opportunities for all youth to feel connected in their communities, schools, institutions can help their self-esteem, growth, and identity. This will enable youth to strengthen their sense of belonging to their communities and expand opportunities for them to become future civic leaders with the capacity to resolve collectively the complex problems that our society are facing in the 21st century.

What does youth civic empowerment in action looks like in San Mateo County?

Integrated

Voter Engagement by Youth Leadership Institute

Youth Leadership Institute (YLI) is a youth-led organizing and

policy advocacy organization that identifies and find solutions

to community concerns. YLI recently started the integrated voter

engagement (IVE) campaign to increase long-term civic

participation by underrepresented communities in San Mateo County

through engaging residents in identifying common issues of

concern, leadership development, organizing and advocacy

skill-building, and voting. YLI seeks to create lifetime voters

and civic engagement leaders by coordinating innovative youth

organizing efforts that focus on leadership development, research

to contextualize local conditions, and advocacy.

Youth

United for Community Action

Youth United for Community Action (YUCA) is a grassroots

community organization that was created in 1994 by and for young

people of color. YUCA offers youth of color who in majority come

from low-income communities, a safe environment to engage in

social justice issues and feel empowered to take civic action.

The organization provides leadership development through

real-time community organizing on campaigns to promote

environmental health, justice, and anti-displacement principles

in land use planning policies and to promote safer school

environments where youth of color can thrive, graduate high

school and prepare for college or a career. One successful

campaign YUCA led was the partnership between Facebook and the

East Palo Alto community, where $20 Million in Affordable Housing

Funds was awarded to the community in 2016.

San Mateo County

Youth Commission

The San Mateo County Youth Commission is an advisory commission

to the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors, established in 1993

to address youth need in the county and provide youth voice in

local government. The Commission consists of 26 members, between

the ages of 13-21, who reside or attend school in San Mateo

County. By placing youth in committees and on County Boards and

Commissions, the Youth Commission increases awareness of and

advocates for youth issues, advises the Board of Supervisors,

presents policy recommendations, and creates projects that serve

the community.

EPACENTER

Arts

The EPACENTER is a creative youth development organization that

encourages East Palo Alto youth to reinvigorate their creativity,

find their potential and impact the world through art and design.

Built as a safe space for youth ages 12-25, the EPACENTER Arts

looks to help youth, especially the community’s youth of color,

to develop their intrinsic voices, creative and critical minds,

and the socio-emotional skills they will need to succeed.

National and International Civic Empowerment Youth Movements

Dreamers:

“Dreamers” is the term used to represent roughly 800,000 young

people who were brought to the US as children and are protected

from deportation by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

(DACA) program. In 2012, President Obama introduced DACA and

offered the children temporary protection from deportation and

status is renewable every two years. Currently, under the Trump

administration, the program and the legal status of Dreamers is

uncertain as Trump pushed for concluding the program on September

2017. For now, Dreamers can renew their status until the final

ruling by the Supreme Court. Immigration advocates, allies, and

young DACA recipients are pushing back to secure their protection

in the only home they know.

#Climateatrike

#FridaysforFuture:

Climate strikes across the world are being led by the 16-year-old

Swedish climate activist, Greta Thunberg. On Friday, 9/20/2019,

the massive coordinated Global Climate Strikes began to motivate

United Nation representatives, who would be at the Climate Action

Summit to act. The Summit will be vital in influencing countries

to commit to earlier climate targets and move toward renewable

energy sources. Greta has activated youth across the world by

using the narrative that young people will inherit a world moving

quickly toward climate catastrophes.

Y-Plan:

Y-PLAN (Youth – Plan, Learn, Act, Now!) is the UC Berkeley Center

for Cities + Schools’ (CC+S) educational strategy that uses the

community as a context for core learning and engages young people

in authentic city planning and policy-making. Their award-winning

educational strategy and action research initiative builds

youth’s knowledge and skills for college, career, and citizenship

while creating healthy, sustainable, and joyful communities. The

Y-PLAN educational methodology seeks to transform public spaces

as a catalyst for community revitalization and educational

reform.

National Alliance for Boys and

Men of Color (ABMoC):

The Alliance for Boys and Men of Color is a national network of

hundreds of community and advocacy organizations who come

together to advance race and gender justice by transforming

policies that are failing boys and men of color and their

families, and building communities full of opportunity. Every

year ABMoC host events like lobby days, summits, and legislative

hearings to build the skills of emerging leaders, center their

voices, and deepen our impact by learning and organizing

together. ABMoC has trained more than 1,000 youth leaders in

California at events like the

Youth Power Summit and supported the leadership and

organizing capacity of more than 200 organizations.

[i] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

National 4-H Council and the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation Partner to Empower Youth in Creating Healthier

Communities. September 14, 2017.

https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2017/09/national-4-h-council-and-rwjf-partner-to-empower-youth-in-creating-healthier-communities.html

[ii] The California Endowment.

Fostering Healthy Youth Development and Leadership. 2019.

https://www.calendow.org/youth-in-action/

[iii] The Women’s Foundation of

California. https://womensfoundca.org/

[iv] Berkman, L. F. Social Support,

Social Networks, Social Cohesion and Health. Soc. Work Health

Care 31, 3–14 (2000)

[v] Nelson, C., Sloan, J., and

Chandra, A. (2019) Examining Civic Engagement Links to

Health. Findings from the Literature and Implications for a

Culture of Health. RAND Corporation

[vi] Hämmig, O. Health risks

associated with social isolation in general and in young,

middle and old age [published correction appears in PLoS

One. 2019 Aug 29;14(8):e0222124]. PLoS One.

2019;14(7):e0219663. Published 2019 Jul 18.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219663 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6638933/

[vii] Alcaraz, KI., Eddens, KS.,

Blase, JL., Diver, WR., Patel, AP., Teras, LR., Stevens,

VL., Jacobs, EJ., Gapstur, SM. Social Isolation and

Mortality in US Black and White Men and Women. American

Journal of Epidemiology, 2018; DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwy231

[viii] Atwell, M., Bridgeland, J.,

Levine, P. “Civic Deserts: America’s Civic Health

Challenge” National Conference on Citizenship, NCOC,

2017.

https://www.ncoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017CHIUpdate-FINAL-small.pdf

[ix] California Trends and Highlights

Overview.” Corporation for National & Community Service,

CNCS. https://www.nationalservice.gov/vcla/state/California

[x] “California – Volunteer Rates by

Year, 1974-2015” Based on Volunteering and Civic Life

in America. Corporation for National & Community

Service, CNCS. https://data.national service.gov/National-Service/California-Volunteer-Rate-by-year/5vsv-a6z9

[xi] Romero, M. (January 2020)

California’s Youth Vote Primary Election

[xii] Romero, M. (October 2019)

Examining San Mateo County’s Adoption of the California

Voter’s Choice Act: 2018 Election Cycle. https://ccep.usc.edu/research-briefs

[xiii] UCB Haas Othering and

Belonging Institute. “Health and Community

Well-being” https://belonging.berkeley.edu/global-justice/islamophobia/resource-pack-us/health-community-well-being

[xiv] Levinson, M. 2010. The Civic

Empowerment Gap: Defining the Problem and

Locating Solutions. In Handbook of Research on Civic

Engagement. Pg. 331-361. Harvard University. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8454069

[xv] The State of Civic Engagement,

PowerPoint presentation by Mindy Romero PhD. Outlines this

typology of civic engagement activities based on the

California Civic Engagement Project. Presentation conducted

on November 15, 2019.

[xvi] Lenzi, M., Vieno, A., Pastore,

M. and Santinello, M. “Neighborhood Social Connectedness and

Adolescent Civic Engagement: An Integrative Model.” Journal

of Environmental Psychology 34 (December 25, 2012):

45–54.

[xvii] Flanagan, C., and Bundick. M.

“Civic Engagement and Psychosocial Well-Being in College

Students.” Liberal Education, Spring 2011, 20–27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6045973/

[xviii] Cedeno, V. “Voting for a

Healthy Community, A Voter Engagement Strategy for the

Alameda County Public Health Department’s AC Votes

Initiative.” Goldman School of Public Policy, University of

California, Berkeley. Spring 2016.

[xix] Kim, S., Kim, C., and You,

M.S. “Civic Participation and Self-Rated Health: A

Cross-National Multi-Level Analysis Using the World Value

Survey.” JPMPH; 2014, 48: 18–27.

[xx] Villalonga-Olives, E., Wind,

T.R. and Kawachi, I. “Social Capital Interventions in Public

Health: A Systematic Review.” Social Science & Medicine 212

(July 14, 2018): 203–18.

[xxi] Copeland M, Fisher JC, Moody

J, Feinberg ME. Different Kinds of Lonely: Dimensions

of Isolation and Substance Use in Adolescence. J Youth

Adolesc. 2018;47(8):1755–1770.

doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0860.

[xxii] Metzger, A., Lauren A.,

Oosteroff, B., et al. “The Intersection of Emotional and

Sociocognitive Competencies with Civic Engagement in Middle

Childhood and Adolescence.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence,

March 2, 2018.

[xxiii] Flanagan, C., and Levine, P.

“Civic Engagement and the Transition to Adulthood.” Princeton

University, The Future of Children, 20, no. 1 (2010):

159–79.

[xxiv] “Risk and Protective Factors

for Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Across the

Life Cycle.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

www.smhsa. gov. Accessed July 29, 2019.

[xxv] Hall-Lande J, Eisenberg M,

Christenson SL, Neumark-Sztainer D. Social

Isolation, Psychological Health, and Protective Factors

in Adolescence. Adolescente. 2007; 42(166).

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9d5e/56a7a01de919ac54c4dee0d3f44014a563e4.pdf

[xxvi] Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide

and Friendships among American Adolescents.

American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):89–95.

[xxvii] Christens, B., and Peterson,

N.A. “The Role of Empowerment in Youth Development: A Study

of Sociopolitical Control as Mediator of Ecological System’

Influence on Developmental Outcomes.” J Youth Adolescence 41

(October 26, 2011): 623–35.

[xxviii] Get Healthy San Mateo

County. School Connectedness and Risky Health Behaviors.

http://www.gethealthysmc.org/post/school-connectedness-and-risky-health-behaviors-0

[xxix] “California Healthy Kids

2017-2018, San Mateo County, Secondary Data.” San Mateo

County Health, Accessed June 28, 2019.

[xxx] Alcaraz, K.I. et Al. (October

16, 2018) Social Isolation and Mortality in US Black and

White Men and Women. Accessed February 24, 2020: https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/188/1/102/5133254

[xxxi] California Healthy Kids

Survey, 2011-2013, 2013-2015, 2017-2018. Analysis done by

Epidemiology division of San Mateo County Health.

[xxxii] California Healthy Kids

Survey of 7th, 9th, and 11th

graders, 2017-2018. Analysis done by Epidemiology, San Mateo

County Health.

[xxxiii] California Department of

Public Health, Office of Statewide Health Planning and

Development, Patient Discharge Data; California Dept. of

Finance, Race/Ethnic Population with Age and Sex Detail,

1990-1999, 2000-2010, 2010-2060; CDC, WISQARS (Apr. 2016).

Analysis done by Epidemiology, San Mateo County Health.

[xxxiv] Guardian of Democracy. The

Civic Mission of Schools. (2011). A report produced by the

Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools in partnership with

the Leonor Annenberg Institute for Civics of the Annenberg

Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania, the

National Conference on Citizenship, the Center for

Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at

Tufts University, and the American Bar Association Division

for Public Education.

https://production-carnegie.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/dd/abdda62e-6e84-47a4-a043-348d2f2085ae/ccny_grantee_2011_guardian.pdf

[xxxv] Youth Leadership Institute,

Surve Findings and Recommendations by Youth Organizing San

Mateo County (YOSMC) and Youth Leadership Institute. 2019.

Accessed August 14, 2019.

[xxxvi] Pew Research Center. U.S.

Politics & Policy. Public Trust in Government 1958-2019.

(April 11, 2019).

https://www.people-press.org/2019/04/11/public-trust-in-government-1958-2019/

Accessed on February 7, 2020.

[xxxvii] Center for Information &

Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. Youth Voting

Rose in 2018 Despite Concerns about American Democracy (April

17, 2019).

https://www.people-press.org/2019/04/11/public-trust-in-government-1958-2019/

Accessed on February 7, 2020.

[xxxviii] Center for Information &

Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. 28% of Young

People Voted in 2018. (May 30, 2019).

http://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/28-young-people-voted-2018.

Accessed on February 7, 2020.

[xxxix] Romero, Mindy. Ph.D.

(February 2019) California’s Youth Vote: November 2018

General Election.

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57b8c7ce15d5dbf599fb46ab/t/5c651f7753450a3dad07f061/1550132771737/CCEP+Fact+Sheet+1+-+2018+General+Election+Final.pdf.

Accessed February 7, 2020

[xl] Center for Information &

Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. Civics for the

21st Century. (September 22, 2017)

http://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/civics-21st-century.

Accessed on February 7, 2020.

[xli] Youth Civic Engagement for

Health Equity & Community Safety.” Mesu Strategies,

Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE). March 2019

http://www.pacefunders.

org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/03/mesuLLC_PACE_YCEveryfinalformat3-2019.pdf

[xlii] Y-PLAN, Center for Cities +

Schools, University of California Berkeley. Accessed August

2019. https://y-plan.berkeley.edu/what-is-y-plan

[xliii] “National Conference on

Citizenship: America’s Civic Health Index, 2007.” Accessed

July 22, 2019.

https://www.ncoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2007AmericasCHI.pdf.